strange-steve

Quantum Brewer

- Joined

- Apr 8, 2014

- Messages

- 6,027

- Reaction score

- 5,805

@Chippy_Tea could you replace the broken image from the OP with this one please:

Hi Steve, planning on doing a Kveik this weekend and have been advised "In terms of water adjustments, I've adjusted to a Bitter so far, but I suspect the profile of Old ale or Wee heavy would work very nicely too."

Could you be so kind to point me in the right direction for RO water. Cheers

Sorry for the delay.Starting my 7th AG brew Sunday. Haven't had any problems I could put down to water quality, but think It's time I learned about basic water treatment.

Any pointers would be much appreciated.

Thanks,

Ian.

Since it's a topic that comes up quite a lot on the forum I thought I'd post a beginners guide to simple water treatment. Rather than delving into the complex chemistry, this is designed to give the basic information to get you started. There is lots of much more in-depth information available online if you want further reading.

The treatment of water for brewing can be broken down into 3 parts:

1. Removal of chlorine/chloramine

2. Adjustment of alkalinity

3. Addition of calcium and ââ¬Åflavourââ¬Â ions

So let's look at each of these 3 aspects, but first some details.

When do I add the water treatments?

Add all treatments to the mash water and sparge water before heating. So fill your HLT with the required volume for the mash, treat it as necessary giving a good stir, then heat to strike temperature. Do the same for the sparge liquor.

How do I measure the acids/salts?

For acids use a small syringe which can usually be picked up free of charge from a pharmacy or chemist. For the salts it's best to use jeweller's scales, but I will give approximate teaspoon equivalents where I can.

1. Removal of chlorine/chloramine

Why?

These are undesirable compounds found in tap water which react with phenols from the wort/hops to create a very unpleasant medicinal/TCP flavour which has a very low taste threshold, and no amount of ageing will remove it. If you use bottled water, this step can be skipped.

How?

There are various methods such as carbon filtration, boiling, aeration etc. which are effective for removing chlorine but not chloramine. These methods can also be time and energy consuming. Therefore the easiest and quickest method is to use campden tablets, which are made from either sodium metabisulphite or potassium metabisulphite.

Simply crush the tablet, add to the mash/sparge water and give it a good stir. Do this before you begin heating the water, it only takes a few minutes for the reaction to take place. Half of a tablet will treat around 35L of water, however using more than required will not have any detrimental effect. So if you are treating say 20L, don't bother trying to add 0.29 of a tablet, just use half.

2. Adjustment of alkalinity

Why?

The main purpose of this is to make sure the mash pH falls within the desired range of 5.2 - 5.8, preferably towards the lower end. This has a number of benefits such as improved enzyme activity, more efficient conversion, better hop extraction in the boil, better protein precipitation, improved yeast health and improved clarity of the finished product to name a few.

Something to bear in mind is that the pH of your water has very little bearing on the pH of the mash, it's all about the alkalinity. If your water's alkalinity is too high, the mash pH will be too high. However to complicate matters a little the grain bill also has an effect. If there are lots of dark or roasted malts in the mash they will lower the pH, therefore dark beers can handle higher alkalinity than pale beers.

Here is a very general rule of thumb regarding alkalinity levels:

For a pale beer <20ppm

For an amber beer ~35ppm

For a brown beer ~75ppm

For a black beer ~120ppm

Something to bear in mind is that if you are making a black or brown beer, but not putting the roasted malts in the mash (eg. cold steeping them) then they will not have any impact on the mash pH and so should be ignored as far as alkalinity adjustment is concerned. In other words, if you were to make a stout with cold steeped roasted malts then you would use an alkalinity level appropriate for a pale or amber beer, depending on the grain bill.

How?

Well first you need to know what your alkalinity is. To do this you need a Salifert KH test kit which will give you an alkalinity value in dKH. Simply multiply that by 17.9 to convert to ppm. Test your water every time you brew, because tap water can be quite variable.(See HERE for the "How to use Salifert test kits" thread.)

Now you have your alkalinity you need to adjust it to a value somewhere close to the values above, don't worry about being exact. Most of the time a mash will naturally end up pretty close to where it should be but this step will help it along. If you have low alkalinity water you may have to increase the alkalinity which can be done by adding sodium bicarbonate (yes the stuff you bake with). Adding 0.1g/L adds about 60ppm alkalinity (1 tsp = ~4g). Note that sodium bicarbonate should not be added to sparge water, only to the mash.

To reduce alkalinity there are again various methods, however I'm only going to talk about using acids because it's the quickest and easiest method. Some of the acids which can be used are lactic, phosphoric, hydrochloric, sulphuric or CRS which is a blend of hydrochloric and sulphuric.

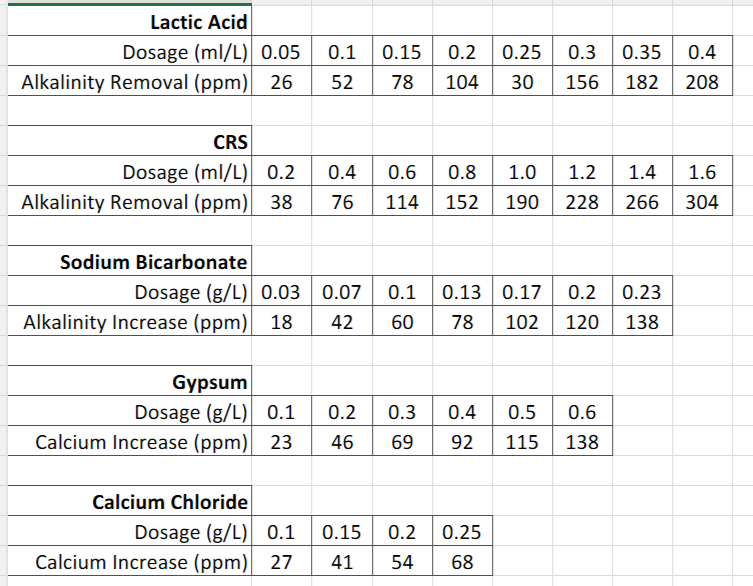

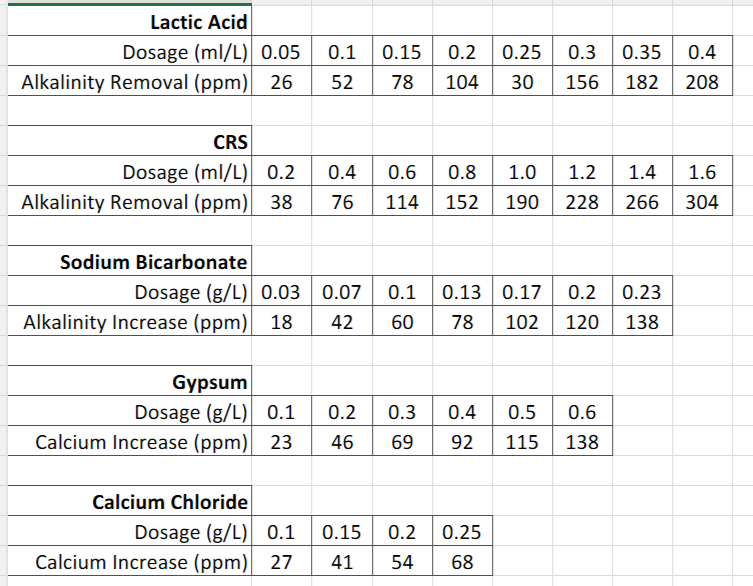

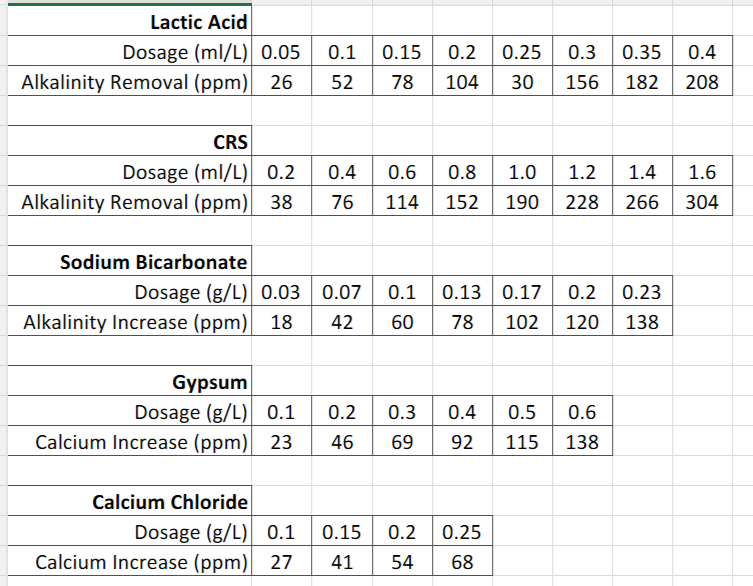

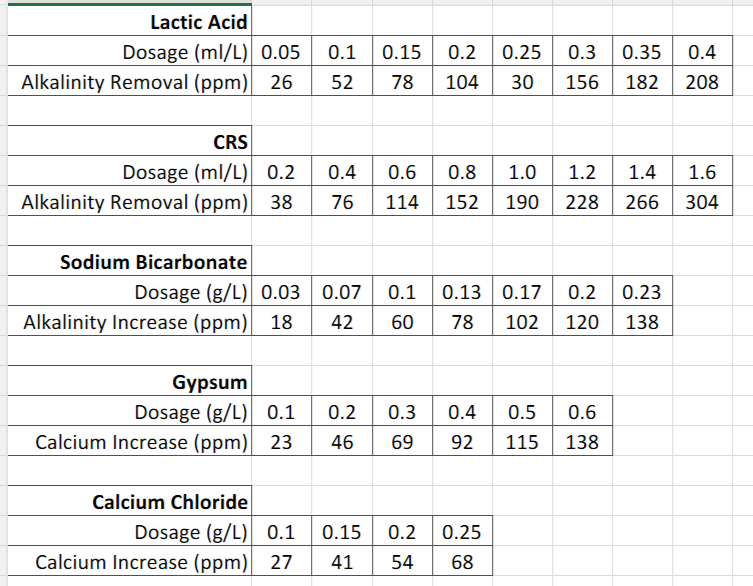

For this guide I will talk about using lactic acid and CRS because they are commonly available in most home brew stores. Firstly lactic acid, now this can have a flavour impact on the finished beer if used in large quantities, therefore I wouldn't recommend using it at more than 0.4ml/L. Lactic acid added at 0.1ml/L will remove about 52ppm of alkalinity.

As for CRS, it is more flavour neutral so can be used in higher quantities. Adding CRS at a rate of 1ml/L will remove around 190ppm of alkalinity.

When using acids to treat the water, always be sure to add it before you heat the water to strike/sparge temperature.

3. Addition of calcium and ââ¬Åflavourââ¬Â ions

Why?

Calcium is an important ion in brewing. It is beneficial for enzyme activity during the mash and is essential for healthy yeast and good fermentation. The desired level of calcium in brewing water is debated somewhat, but 40ppm should be considered a bare minimum. Some sources suggest 100 or even 150ppm as a minimum, but the malt should provide enough calcium to ensure good yeast health so personally I usually aim for around 100ppm as a minimum. One exception to this may be when brewing a pilsner, in which case it's a good idea to keep the mineral content low and aim for around 40-50ppm of calcium. This is lower than the calcium content of many people's tap water, so it may be necessary to use bottled water (such as Tesco Ashbeck) or RO water.

How?

Calcium is added in the form of gypsum (calcium sulphate) and/or calcium chloride. So which of these should I use? Well this is where the ââ¬Åflavourââ¬Â ions, sulphate and chloride, come into play. Hoppy beers benefit from have a higher sulphate content, because this ion will give a dryer finish and it enhances the perception of bitterness in a highly hopped beer. Chloride on the other hand works better in a malty beer because it accentuates sweetness and fullness of flavour.

So put simply, use gypsum for hoppy beers like IPAs and use calcium chloride for rich, malty beers like mild and Scotch ale. If brewing a more balanced beer like an English bitter, use a combination. One notable exception to this is the New England IPA, which despite being extremely hoppy, tends to use chloride rich water rather than sulphate, so calcium chloride should be used rather than gypsum. This adds to the full bodied, juiciness common to the style.

Add enough to bring your calcium up to around 100ppm or more using the following information:

Gypsum added at a rate of 0.1g/L adds ~23ppm of calcium (1 tsp = ~4g). Use at a maximum rate of 0.65g/L.

Calcium chloride added at a rate of 0.1g/L adds ~27ppm of calcium (1 tsp = ~3.4g). Use at a maximum rate of 0.25g/L.

But how do I know what my starting calcium level is? Well there are a few ways. Firstly you can contact your water supplier and they will send you a water report, however the figures on this are often mean values and the calcium level can be quite variable like the alkalinity. Another way to get a rough figure for calcium is to multiply your alkalinity value in ppm by 0.4. This won't be entirely accurate either but it should be fairly close. Thirdly, the best way is to get a Salifert Ca test kit. This way you can test the water each time you brew and it'll be more accurate than the other two methods.

Putting it all together

So let's look at a couple of examples now which will hopefully make all this a little clearer. I've used a couple of slightly more difficult examples to show how they can be treated with the above method. These examples assume you have tested for alkalinity and calcium.

Brewing a stout with low alkalinity water

I'm using the values for Tesco Ashbeck's water profile for this because it has a very low alkalinity of ~20ppm and 10ppm calcium. So firstly, as you can see above, a black beer needs an alkalinity of ~120ppm so we need to add 100ppm. As you can see from the table below, adding sodium bicarbonate at at a rate of 0.17g/L is pretty close.

Now we need to increase calcium to around 100ppm. Because this is a malty beer, we'll use calcium chloride. Adding calcium chloride at it's maximum dosage of 0.25g/L will add about 68ppm which isn't quite enough, so adding 0.1g/L of gypsum as well will add an extra 23ppm. So that's 91ppm added to the original 10ppm.

Now just plug the numbers in, so if you have 12L of mash water that equals 2g of sodium bicarbonate, 3g of calcium chloride and 1.2g of gypsum.

Say you have 20L of sparge water, that will require 5g of calcium chloride and 2g of gypsum. Remember alkalinity increase is not required for the sparge water, so no sodium bicarbonate is added here.

Also don't forget to add the crushed campden tab, about half to the mash water and half to the sparge water.

Brewing a pale ale with high alkalinity water

For this example lets assume an alkalinity of 250ppm and calcium of 100ppm, and a 100% pale malt grist. So for a pale beer we want around 20ppm of alkalinity which means removing 230ppm. This is probably over the taste threshold for lactic acid so I wouldn't recommend using it for this, CRS would be better. Looking at the table below, an addition of 1.2ml/L of CRS will reduce the alkalinity by the correct amount.

As for calcium, although the level is already at the minimum 100ppm, I'd still recommend adding some gypsum to accentuate the hops. An addition of 0.2g/L will bring the calcium up to around 146ppm while adding sulphate to make the hops stand out a little.

So plugging those figures in, a mash water volume of 12L would require 14.4ml of CRS and 2.4g of gypsum. For 20L of sparge water, add 24ml of CRS and 4g of gypsum.

Again don't forget to treat the water with campden tabs.

So that's it, pretty straight forward. Just remember the 3 main points of water treatment, remove chlorine, adjust alkalinity, add calcium salts. Any questions, comments or corrections please let me know below.

You can use the table below to work out your required dosage of acids and salts if you don't want to do the maths :)

Thanks to Bru'n Water for some of the figures regarding addition rates.

TBH I don't really know enough about the style, what sort of flavour profile are you expecting?

To be honest Bri, your water doesn't look too bad for a stout, maybe just a little half teaspoon of calcium chloride flakes in the mash is all I would add to that. It'd be worth testing your mash pH about 10 mins or so after dough in, although saying that I wouldn't really trust those paper strips anyway.

The calcium chloride will increase the calcium a bit, but that's not why I suggested adding it in this case, because you have plenty of calcium. It's to increase the chloride which will accentuate the malt flavours in the finished beer.Great response pal,

You'll understand the complexity of all this doing this n that gets me confused!

If I take it small steps at a time...it's ok!

Looking at the style diagram Brown beer 75ppm alkaline

And maybe 100ppm with calcium.

Am I right in saying this:

Happy with the alkaline (80ppm)

Adding half t spoon calcium chloride to take the calcium reading down to 100ppm (from 130ppm)?

I know now waiting for my pH meter batteries, for the pH reading in the mash!

I know it important in the strike water to get the pH level 5.2-5.6 pH, for the Beta & Alpha enzymes to doing its job on the sugars...if you know what I mean lol!

So I've got the strike water sorted and the pH level within the range!

Finished mash & sparge...taking a pH reading befor boil and seeing the pH reading??

After that cloudy in my small mind!

Do I adjust to the pH level of 5.2-5.6?

Looking at the grains some more the pH level will change from the grains used:

10l batch

Marris Otter

Roasted barley

Crystal 50l

Flaked Barley

Adicic Malt

Oat husks

Ok this is a bit different because usually the low pH isn't from water treatment but from naturally produced lactic acid, however there are a few ways to make a Berliner weisse. These are a few common methods:Second question the Berliner Weiss needs to be think at the end of sparge 4.5 pH (from David heaths vid)

How I can adjust the level?

And the Pmm levels for the style (alkaline and calcium levels) to the say 10.6L strike water?

It'll be 50/50 german pilsner/german wheat malt.

Mind his process with cling film with one hand going to be fun!!!

Ordered my grains etc..be here Monday!

I'm getting there, if I learn adjusting, adding this n that be less of skill fade..

The calcium chloride will increase the calcium a bit, but that's not why I suggested adding it in this case, because you have plenty of calcium. It's to increase the chloride which will accentuate the malt flavours in the finished beer.

The only pH you need to be concerned with is the mash pH which is usually measured 10-15 mins after mashing in. As long as it's somewhere between 5.2 and 5.8 then you don't really need to worry, although if you can get it around 5.3 or 5.4 then even better. Your water has moderately high alkalinity which usually will cause a higher pH than desired, but the crystal malt, acid malt and roasted barley in this beer will help lower it to where it should be.

It's all guesswork though, because the reactions taking place in the mash are very complex, which is why the best thing to do is measure the pH, take good notes and try to adjust the next time. I wouldn't advise trying to chase pH during the mash if it's not quite right. Just let it be and adjust your additions accordingly on the next brew.

Ok this is a bit different because usually the low pH isn't from water treatment but from naturally produced lactic acid, however there are a few ways to make a Berliner weisse. These are a few common methods:

1. The easiest way is to brew the beer as normal then add lactic acid directly to it to get the desired level of sourness. However doing it this way won't give you the same complexity of flavours as the other methods.

2. As above except acid malt is used in the mash as the source of lactic acid.

3. Sour mash by reducing the temperature at the end of the mash to about 40ð then adding lactobacillus, leaving for a day or two then sparging and boiling (or not) as normal. This will give a better flavour but is a little more risky as the mash can go off if the wrong bacteria get hold.

5. Mash, sparge and boil as normal then pitch some lactobacillus along with the yeast. You can use a commercial strain of lacto such as WLP677, or you can add some natural yoghurt or L. Plantarum tablets.

I hope that's helpful. FWIW I used option 4 and it turned out really well, a great summer beer.

It could be a few months, but it'll be well worth the wait.

Another way to get a rough figure for calcium is to multiply your alkalinity value in ppm by 0.4. This won't be entirely accurate either but it should be fairly close.

Use the pre treatment value, so 260 alkalinity means about 104ppm calcium.

I wonder what people's thoughts are on the impact (if any) of using dehusked roasted grains in a stout. I'm very sensitive to astringency in beer so I plan to try dehusked roast barley which is supposed to lower the risk of that. What I don't know is whether that also lessens the impact that dark grains normally have on alkalinity or if these things are totally independent. Anyone have any thoughts?

Sent from my iPhone using Tapatalk

Enter your email address to join: